This article was originally published on LinkedIn on November 19, 2023.

Remember visiting your local dairy for an ice cream or a lolly mix as a kid? If you're like me, you'll remember walking, scootering, or biking to your local dairy. In my case, either my local dairy or supermarket 800m away from my family home in Waihōpai Invercargill. The proximity of these and several other businesses means they were accessible for me and my family by a small walk and bike ride.

Now, grown up and live in the city centre in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. I have the opportunity to access these amenities within walking distance with a dairy and coffee stand on the ground floor of my apartment building, which is helpful for the mornings when you find out you have no coffee or milk. I also have supermarkets, retail stores, and other significant amenities on my doorstep.

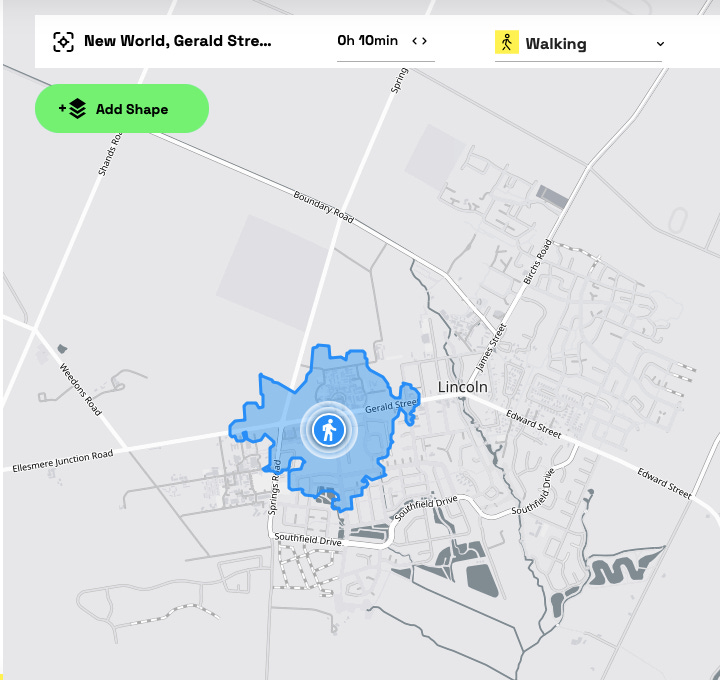

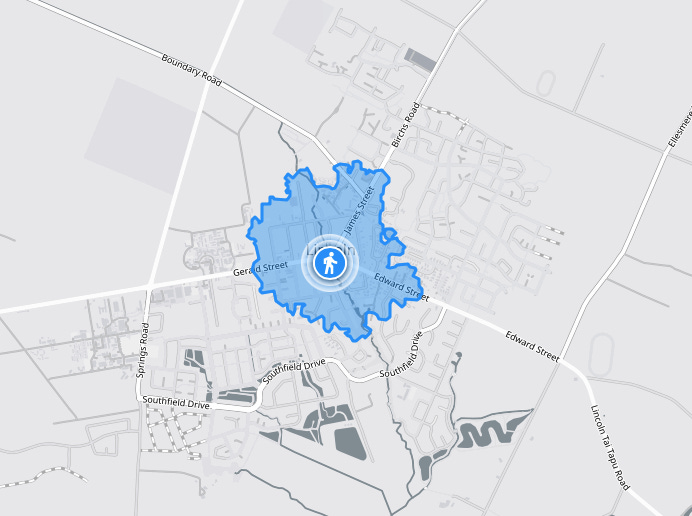

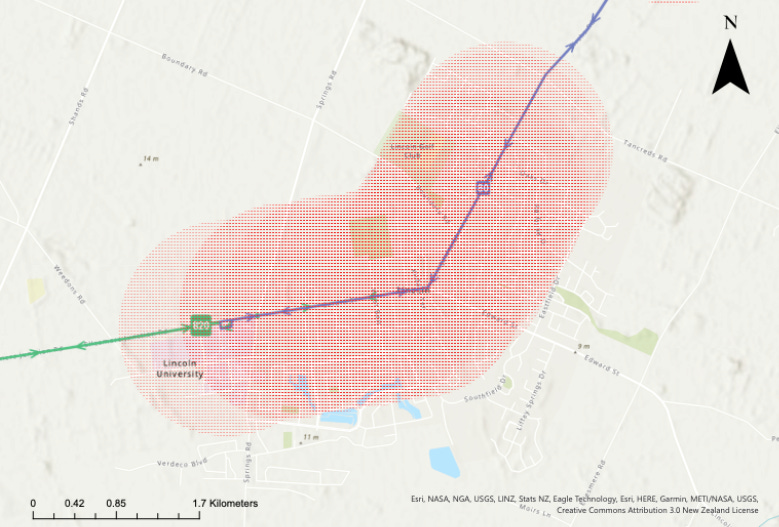

However, some who live further away from the city centre, as our cities are sprawled out, do not have easy access to these amenities by walking or cycling and depend on a car to access them. An example is in Lincoln, 20km southwest of Ōtautahi Christchurch. The part of Lincoln where I lived during my studies at Lincoln University was within walking distance of the town centre, with dairies, pharmacies, and eateries. But, for those living in the new subdivisions that were developed from the early 2010s onward as the township sprawled to support its increased population following the 2010- 2011 earthquakes, walking or cycling to the town centre or the local supermarket from those areas was less attractive.

This is because most of Lincoln is not within a 10-minute walk of the local supermarket or the town centre. Also, due to the limited commercial development built in those subdivisions to support those communities, they experienced consenting issues like a proposal for a Countdown supermarket, which ended in the resource consent being declined. The town centre and near the New World supermarket are the only areas where the township's major amenities are located. There's some cycling infrastructure from the Little River Rail Trail, which runs through the township. Gerald St, the main road through Lincoln, needs separated cycleways. I felt unsafe biking on Gerald St as cyclists shared the road with buses and trucks, with reports of incidents involving cyclists and cars. Finally, some parts of Lincoln are not within 800m of a bus stop for routes 80 and 820, which only run every 30 minutes and an hour, respectively. As a result, trips to the town centre or supermarket are likely made by car.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, almost half of household car trips are under 6km, with 1/3 under 2km. Short-distance car trips use more fuel, emitting more emissions and pollutants. In the central government's emission reduction plan, Tier 1 cities must reduce vehicle kilometres travelled (VKT) from light vehicles by 20% by 2035. On top of that, some cities also have individual targets to reduce VKT, like Tāmaki Makaurau, which aims to reduce VKT from light vehicles by 50% by 2030, as outlined in the Transport Emissions Reduction Pathway (TERP).

To help reduce VKT, our cities need to be more compact. This can be achieved through reform to our zoning rules to enable the construction of apartments and townhouses. Recent legislative changes, like the National Policy Statement for Urban Development (NPS-UD), will upzone to enable residential developments up to six stories around town centres and rapid transit stations. The Medium Density Residential Standards (MDRS) allow for three dwellings of up to three stories on a site without resource consent. These changes will encourage more density in major cities in Aotearoa. Despite these legislative changes, another piece needs to be added to these reforms: enabling mixed-use zoning.

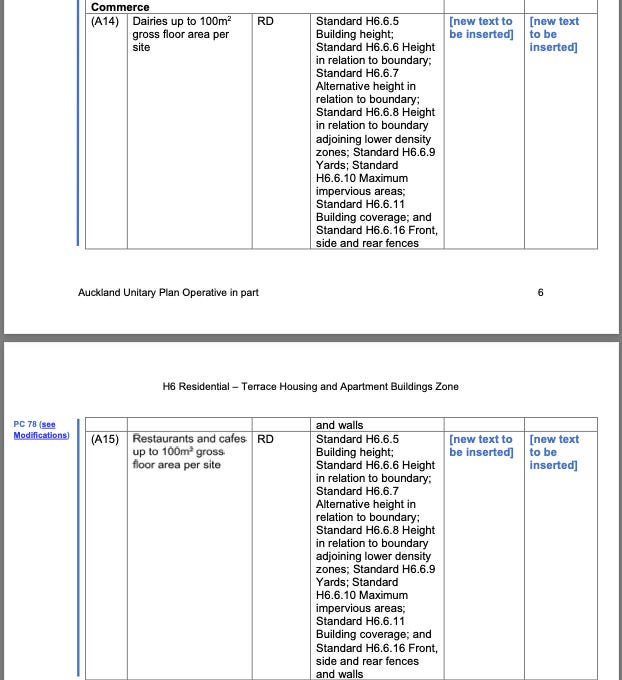

In Tāmaki Makaurau, in the Unitary Plan (AUP). Mixed-use activities are permitted in Business-Mixed Use, Business-City Centres, Metropolitan Centres, or Town Centre Zones. However, in areas zoned Terrace Housing and Apartment Building (THAB) and Mixed Housing Urban, commercial activities are not permitted and require resource consent. This makes getting approval to build mixed-use development more complex as it goes through our planning framework under the Resource Management Act (RMA). Our planning framework focuses on the adverse effects of an activity (e.g., effects on the character of the area, effects on traffic) rather than outcomes and how that activity contributes to achieving local and central government policy, such as emission reduction and mode shift to active modes.

Enabling mixed-use development creates more amenities to support our neighbourhoods. Having dairies or "metro" supermarkets are located near your home, where you can get a loaf of bread, milk, or a missing ingredient for dinner within a short walk, bike ride, or a trip downstairs. It also supports social and economic well-being (e.g., cafes, eateries, retail), which creates places to gather with friends and whānau over a coffee or lunch and support local businesses as they get on their feet.

More mixed-use developments in our cities can unlock opportunities for transit-oriented development (TOD) around our train stations and frequent bus corridors. This would improve people's access to retail and commercial activities on the way to their bus or train and create town centres with a mix of housing, retail, and commercial offices close to public transport stations and interchanges.

Enabling mixed-use development assists with our goals of reducing VKT. More amenities can be built and integrated into residential developments. It means people will be within walking distance or accessible by cycling and public transport, especially as our cities get denser. Mixed-use developments can help reduce VKT in areas with few alternatives to the car. Especially those trips under 6km can be replaced with walking or cycling within their local neighbourhoods, resulting in car-lite lifestyles as most major amenities are near their home.

National, the major party to make up the incoming government, signalled during the election campaign changes to the NPS-UD to enable mixed-use development. One of the three laws replacing the RMA, The National and Built Environment Act (NBA), will see the National Planning Framework move from an effects-based to an outcomes-based framework, hopefully resulting in more decision-making around activities aligning with the goals of policies and strategies and other relevant legislation.

Meanwhile, the future of MDRS is yet to be determined following National's reversal of its support and opposition from ACT, another party to make up the incoming government. My view is that MDRS should stay as our cities benefit from density. More density in our cities increases housing choices for people, reduces housing prices and rents, reduces costs to build and maintain infrastructure and reduces urban sprawl. If MDRS remains, one of the changes that should done to strengthen it is enabling mixed-use developments. This could be achieved in three-storey developments by having shops with apartments above or townhouses behind the shop, alongside other changes that could be made to strengthen MDRS, as explained in an alternative MDRS that was put together by housing advocacy group, The Coalition of More Homes.

We all have experienced the benefit of being near significant amenities vital for everyday living and delivering social and economic well-being to our communities, whether you live close to a dairy or cafe or stay in a hotel in dense environments while on holiday. By enabling more for these amenities close to our homes as cities intensify. We can unlock the potential of more walkable neighbourhoods and their amenities, whether it's a dairy, a cafe or a clothing store. It can easily accessed by a short walk or bike ride, reducing our transport emissions, travel costs and VKT. This, alongside changes needed to our streets (as discussed in my previous article), can help fill the necessary pieces to create more vibrant and sustainable urban environments in Aotearoa.